Stephanie Hayden, part 2

Stephanie Hayden has threatened to sue me for defamation if I publish this. I publish this in the public interest as a citizen journalist given Hayden is a lawyer, and a controversial self-styled public figure, whose conduct has raised many questions and engendered much spirited debate from members of the public.

I also publish this to stand up for freedom of expression and freedom of the press. It is important that our society can ask hard, difficult questions of self-styled public figures on controversial topics such as serial litigation involving people exercising freedom of expression rights as well as other uncomfortable matters.

I A Legal

On 3 December 2013, an entity called I A Legal was instructed by a Mrs Clark to take over a claim for possession of a property and unpaid rent, issued at Torquay and Newton Abbot County Court in the matter of Ancilla Clark v (1) Thomas Hardy (2) Henry Maloney (3) Alexander Laine-Hardy. I shall hereby call it the Hardy matter.

The person at I A Legal responsible for the matter was one Anthony Halliday, described as a “Member of the Chartered Institute of Legal Executives” and later on in the same letter as a “fee earner” by inference.

A fee of £350 plus VAT was agreed upon.

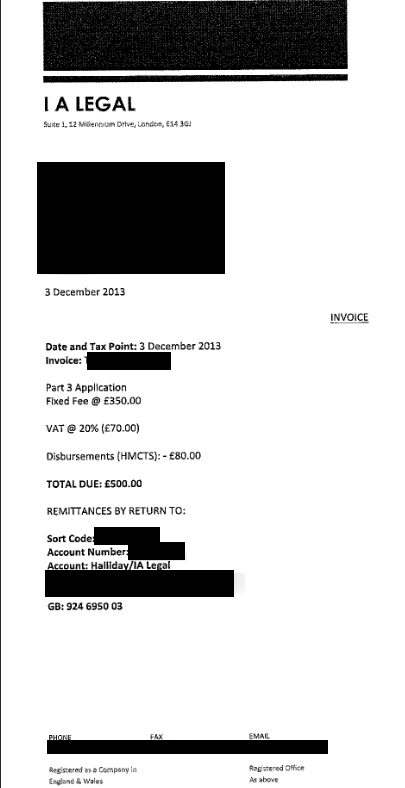

I A Legal claimed to be a registered company. Documentation issued by I A Legal clearly stated “Registered as a Company in England and Wales”, but no company registration number was shown. The registered office address was stated to be Suite 1, 12 Millennium Drive, London, E14 3GA.

A VAT number of GB 924 6950 03 was provided on the invoice. This will be relevant later on.

Initially, I had struggled to find the existence of a company called “I A Legal” with ties to Anthony Halliday. Shortly before the publication of this article, however, I was provided with details of a company called Inter-Alia Legal Limited (company number: 08178039), the director of which was Anthony Halliday. I believe this is the company referenced as “I A Legal” because, although the registered office doesn’t match up with the documentation (I suspect the information at Companies House was simply never updated), it was established on 13 August 2012 and dissolved on 25 March 2014 for failing to file accounts—so it was operational during the relevant period, and it is directly tied to Anthony Halliday. The dissolution date also ties in with another company, below, being incorporated a month later by the same person.

In contemporaneous correspondence the following year, it appears that the telephone details used for I A Legal were also used for a company called Common Law Limited (company number 09009416) owned by one Anthony Halliday, incorporated on 24 April 2014 and dissolved on 1 December 2015 for failing to file accounts. I strongly suspect this company was set up to carry on the work of I A Legal after that company got dissolved on 25 March 2014.

Additional evidence indicates that an email address under the name of Steven Hayden, in addition to a separate address being used by Anthony Halliday, was also operational. In emails I have seen, the impression the correspondent got from reading emails from both was that these were the same person using two different names and email addresses (Hayden and Halliday) as the correspondent described them as having “very similar writing styles”. It reminds me of the behaviour exhibited at a different company owned by Hayden in my previous article where Anthony Halliday was one identity and then, presumably, Stephanie Hayden would have been another identity.

Below you can see the invoice issued by I A Legal in the Hardy matter. While this copy is in black and white, the distinctive letterhead and style have already been seen elsewhere: in documentation from a different company owned by Hayden, covered in my previous article.

VAT

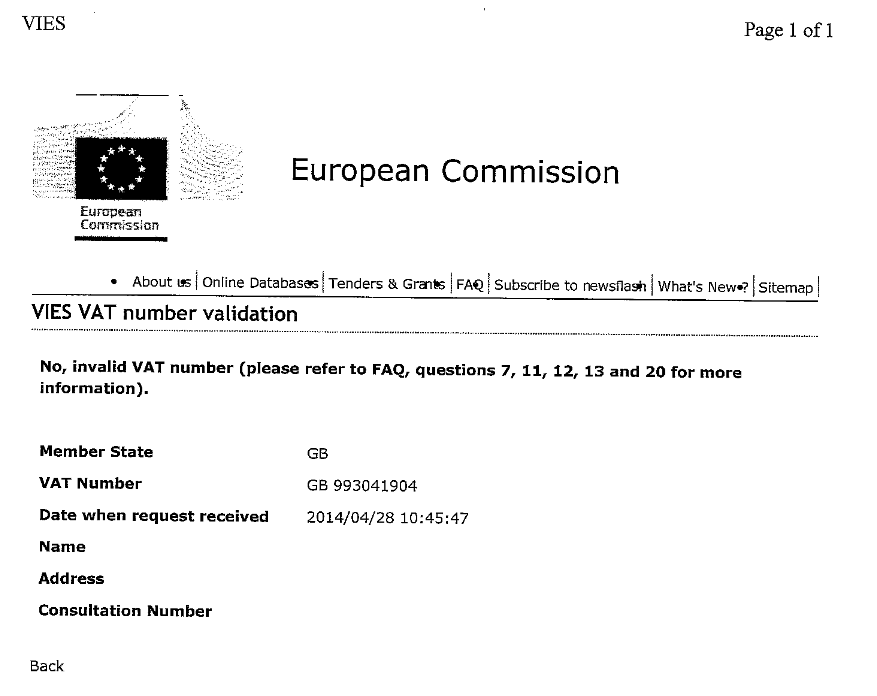

You will remember earlier that I mentioned the invoice issued by I A Legal both charged VAT and had a VAT number on it. Indeed, you can see it for yourself above. A contemporaneous search of the VIES VAT identification database operated by the European Commission returned no results for that number and described it as “invalid”.

It is therefore apparent that VAT should not have been charged on the invoice presented by I A Legal, because the company was not registered for VAT under that number.

It appears there is a pattern of charging VAT when not entitled to do so. This could amount to fraud. It happened to a client in the previous article some years later under a different company run by Hayden.

Hayden has a number of convictions for dishonesty, as read out in open court on 7 February 2020 and reported by the Daily Mail at the time, and it is fair to ask: why, on two separate occasions far apart in time by a number of years, has VAT been charged by a company owned by Hayden that is not entitled to do so?

Those convictions are all spent and Hayden is rehabilitated under the Rehabilitation of Offenders Act 1974.

A further search was carried out on 28 April 2014 (shown below) to check a VAT number purportedly used by Common Law Limited but again, no results were returned. So, if VAT were being charged by Common Law Limited, again it shouldn’t have been.

CILEX membership

In open court in the matter of Knapper v Clark on 21 July 2014 before District Judge Taylor, Halliday stated that Halliday was a member of CILEX and provided the membership number 50121441.

Halliday was admitted to CILEX under the name Steven Paul Hayden in October 2008 and was given that number. For clarity, Halliday changed Halliday’s name by deed poll to Steven Paul Hayden on 28 July 2005. However, Hayden was not the name that Halliday used when appearing in court.

Enquiries made of CILEX at the time confirmed that, when Halliday self-declared as a member of CILEX, this was not strictly true. Halliday had not paid the membership subscription due and, until the subscription was paid, was not entitled to self-describe as a member.

In the hearing on 21 July 2014, the transcript documents that Halliday self-described as a layperson representing the litigant in person with the associated right of audience as set out in CPR Practice Direction 27A, paragraph 3.2.

That is perfectly legal and legitimate, and no issue is taken with that. However, it is alleged that Halliday, prior to the hearing, attempted to enter the advocates’ room in the court building and was denied. Why would a layperson (as Halliday rightly was) representing a litigant in person try to enter an area of the court reserved for barristers?

This was all documented in a letter dated 3rd December 2014 issued by HHJ Cotter QC, the then Designated Civil Judge for Devon and Cornwall.

Conducting litigation: a reserved activity

In the Hardy matter above, I have seen a letter where Halliday uses the term “Your previous solicitors”. This is misleading in this context because it gives the impression to the client that Halliday was qualified to act as the current solicitor. This is not true: Halliday was not a solicitor at the time the letter was written, and is not a solicitor now.

Later on in the same document, the line “once we are in funds we will be able to prepare and submit your application to the court without any delay.” appears. This is relevant for reasons I shall explain later on.

The conduct of litigation is a reserved legal activity under the Legal Services Act 2007. This means it can only be carried out by an authorised person, such as a solicitor, a barrister, a CILEX Authorised Practitioner, or someone who otherwise has an entitlement to do so (e.g. the courts specifically grant them the right to conduct litigation in a given matter, which makes that person exempt from needing to be authorised).

The meaning of “conducting litigation” is not specified in the Act, but clarification has finally been set out by the High Court in Baxter v Doble & Anor [2023] EWHC 486 (KB) and it has been established in Gregory v Turner [2003] EWCA Civ 183 that a litigant in person cannot delegate their right (by being a party to proceedings) to conduct litigation to an agent unless that agent is authorised to conduct litigation in their own right.

In other words, you cannot delegate your right to conduct litigation (because you are suing or being sued by someone) to me, unless I am authorised to conduct litigation in my own right (I am not). It would be a criminal offence for me to do that when I am not authorised or exempt from being authorised, as well as being a contempt of court.

Halliday was not entitled to conduct litigation because Halliday was not an authorised or exempt person at the relevant time, nor had Halliday been granted an exemption by the court in that case, and the client could not delegate such a right to Halliday for the reasons I have explained above.

While it is fair to concede that the High Court only clarified the law last year, it seems obvious that activities that form a part of the process of litigation (after, or at the point, proceedings have been issued) would naturally come within the ambit of conducting litigation. It would be highly unusual if, for example, preparing and filing an application on behalf of a client did not amount to conducting litigation—or equally if managing a case on behalf of a client, the same way a solicitor would, did not count either, and as the High Court decided, clearly cannot be what Parliament intended when enacting the Legal Services Act 2007.

Even without the welcome clarification of Doble, case law indicated that the conduct of litigation included taking action on “formal steps” required in the process of litigation, as set out in Agassi v HM Inspector of Taxes [2005] EWCA Civ 1507.

Furthermore, in the case of MK v JK [2020] EWFC 2, the court held that an unqualified person drafting and filing a document (such as an application) with the court would constitute carrying out reserved instrument activity (of the sort raised in my last article). While this is a separate activity, it indicated the clear direction of travel of judicial thinking from senior judges prior to the decision in Doble: unqualified people are not entitled to carry out reserved legal activities like drafting and filing documents, let alone to conduct litigation.

It is also the opinion of the Bar Standards Board that conducting litigation includes, but is not limited to:

- Beginning court proceedings by filing details of the claim (e.g. the claim form, particulars of claim) at court or making an application for a court order

- Filing an acknowledgment of proceedings

- Giving their address as the address for service of documents

- Filing documents at court or serving documents on another party

In this instance, preparing and submitting an application to the court (as mentioned earlier in the letter: “once we are in funds we will be able to prepare and submit your application to the court without any delay.”) would come under the conduct of litigation because it would be, at the very least, “filing documents at court”, and would certainly fall within the ambit per the Doble judgment if carried out today.

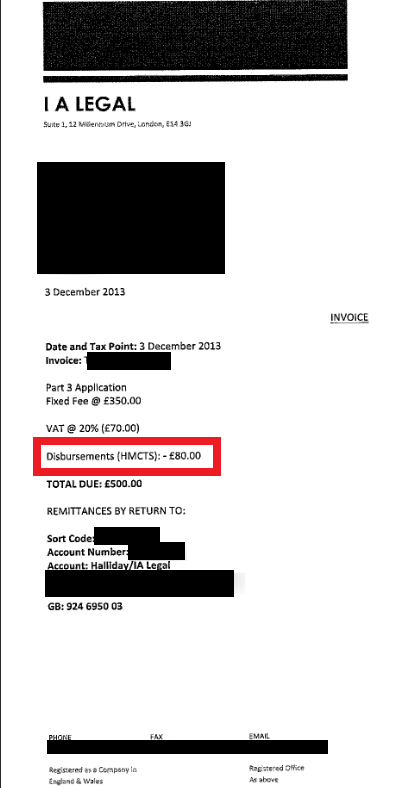

Further weight is added to this notion when you go back and look at the invoice. There is a line item for “Disbursements - HMCTS” of £80. That is the court fee that was applicable for a Part 3 application at the time.

Why did Halliday require the client to pay £80 for a HMCTS (HM Courts and Tribunals Service) fee? If the client submitted the application to the court themselves, they would pay the fee to the court at the same time. There would be no need to give I A Legal £80 to then pay the court. Doing that doesn’t make any sense in that scenario.

It would make sense if the application was submitted on behalf of the client. The court no longer appear to have a copy of the case file so we don’t know who actually submitted the application. However, the evidence shows the intention was there: it’s documented in the letter, and the associated court filing fee is raised as part of the invoice.

Conducting litigation when not authorised or exempted by law is a criminal offence and a contempt of court.

Hayden chose not to provide a reply, a quote, proof of legal qualifications entitled to conduct litigation, etc. when approached prior to publication. No factual inaccuracies were identified by Hayden. No evidence to disprove anything raised in this article was provided.

Hayden chose to state that Hayden would be adding this article to the list of claims against me (including defamation, harassment, etc.)

As ever, I have assembled the evidence and the facts. It is now for you to make your own minds up.